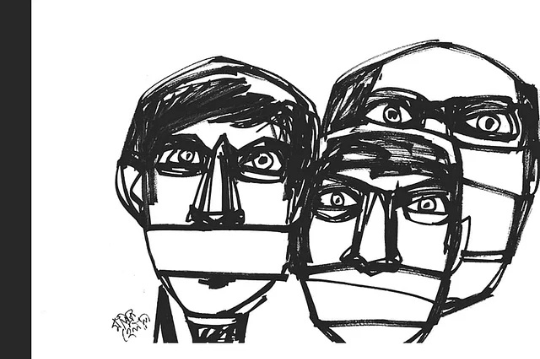

Gagging Young Voices: The Unreasonable Nature of Our Digital Laws

Published on 04/10/2022

Zillur Rahman

Social media is a leviathan that all modern governments are struggling with. The increasing internet access in Bangladesh has allowed almost everyone to throw their two cents into the court of public opinion. Governments understand the enormous power of social media quite well. It can also be argued that the quality of political discourse online has declined dramatically in terms of usefulness and civility. There can undoubtedly exist social media posts that are made with the intent and/or the potential to harm national security, friendly relations with foreign states, public order, cause defamation, or incite offence. It is up to the government to decide on reasonable restrictions imposed by law to handle these situations. This is, in essence, the term set in Article 39(2) of the constitution.

However, the key words here are "reasonable restrictions." When talking about the effects of the Digital Security Act (DSA) and the potential impact of the upcoming data protection legislation, it is vital to ensure that the regulations imposed on freedom of expression by these laws remain reasonable. Indeed, it is the current unreasonable nature of the DSA that is being challenged when legal scholars and experts speak out against the overreaching power given to law enforcement agencies through this law.

As it stands now, any person whom law enforcement authorities deem to have breached the DSA will be arrested without a warrant, even if they are underage children.

On September 20, 2020, a person wrote a comment on late Hefazat-e-Islam Ameer Allama Shafi on Facebook. Local authorities deemed this post offensive, and the person was promptly arrested under the DSA. Meanwhile, this post was shared by a 15-year-old, 18-year-old Abdullah Al Mamun, and 18-year-old Ahsan Ullah. All three boys, including the 15-year-old, were also arrested simply for resharing the post on their private profiles.

On March 20, 2021, A college student named Humayun Kabir was arrested under the DSA after he posted a video on Facebook opposing Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi's visit to Bangladesh. The college student was arrested and sent to jail in a case filed by a sub-inspector of the local police station.

On June 20, 2020, a Class 9 student was arrested under the DSA for criticising the government's move to increase tax on mobile phone call rates by making a taunting post directed at Prime Minister Sheikh Hasina. The secretary of Jubo League's Habirbari union unit in Mymensingh filed a case against the teenager when the status went viral. After his arrest, the 14-year-old was sent to the juvenile correctional centre in Gazipur.

I leave it up to readers to decide if the use of the DSA in each of these cases was reasonable or not.

The DSA, according to Prof Ali Riaz of Illinois State University, has been widely employed by government organisations and individuals in Bangladesh. Although the government stated that the law would provide individuals with security, the bill was written in such a way that it might be used to suppress critics and criminalise dissent. According to his research paper titled "The Unending Nightmare: Impacts of Bangladesh's Digital Security Act 2018," published by the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS), data gathered and analysed from reports between January 2020 and February 2022 revealed that the legislation had been weaponised. Journalists and politicians were disproportionately victimised by this law, and the younger population was vulnerable to rampant abuse of the law. The research also pointed out that although they are not the aggrieved party in these claimed wrongdoings, the vast majority of accusers in lawsuits brought under the statute are members of the ruling party and its supporters.

The ambiguity of several legal provisions in the DSA has resulted in a scenario of vigilante justice. Often, falsified claims have been used to justify verbal lynching and social ostracism. Commenting on social media, particularly Facebook, has become dangerous under this rule, and criticising government leaders has placed people in court and in jail.

Although the government has recently begun to acknowledge some misuse of the law, the data strongly suggests that it was widespread. The law undermines the country's commitment to international law and norms of fundamental rights and violates the human rights guaranteed by the constitution.

Additionally, the government is now working on a new data protection legislation that would compel mandatory localisation of personal and non-personal data in Bangladesh. Notably, the necessity for localisation extends to user-generated material, implying that all interactions via social media platforms, instant messaging and video communication apps, emails, and user metadata would have to be stored in servers and data centres within the country.

With the new online content control and localisation law, service providers such as Facebook and YouTube are required to keep user information in Bangladesh and cooperate with the government's request to erase, trace, and reveal it to state authorities. With broad exemptions granted to government authorities and no procedural safeguards or independent oversight mechanisms in place, there are concerns that these frameworks will open up new avenues for state agencies to monitor and intercept content and communications in accordance with the existing surveillance laws.

Needless to say, this would inevitably restrict free speech by encouraging a culture of self-censorship and digital authoritarianism, and increase the dangers of coercive actions against journalists, activists, dissidents, and the general public for expressing unpopular opinions or dissent.

All indications point to the government consciously or unconsciously acting in a way as to undermine people's right to privacy and free speech. A discussion needs to take place on where the lines of reasonability are drawn. When new laws are made, there has to be sufficient consideration about balancing citizens' rights with protecting national security. As for the DSA, its clauses need to be made more specific and not so all-encompassing. The power vested by the act to arrest without a warrant needs to be brought under oversight.

Ultimately, I believe it would be better for the people of Bangladesh if the Digital Security Act was repealed and a new, more reasonable data protection law was instated.

Zillur Rahman is the executive director of the Centre for Governance Studies (CGS) and a television talk show host. His Twitter handle is @zillur

News Link: